I Am Not An Impostor

- By

- Jayne Rooke, Contributor

- Posted

- Monday, May 3, 2021

Impostor syndrome (also known as impostor phenomenon, impostorism, fraud syndrome or the impostor experience) is a psychological pattern in which an individual doubts their skills, talents or accomplishments and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a "fraud".

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impostor_syndrome

In The Beginning

The fear of 'being found out' or 'not being good enough' is so strong and real to the Impostor that they never question it. —Jayne Rooke

I became aware of the term impostor phenomenon[1] (IP) back in 2006 when I also first experienced a new developmental approach called coaching. It was to be the start of a continuous, sometimes joyous, but more often than not painful journey to self-awareness and a change in career. My coach highlighted the possibility that I was limiting myself through a total lack of belief in myself and my capability. She introduced a great article from the Harvard Business Review[2] on Impostor Syndrome and the rest as they say is history.

Why is it so important in the field of coaching? Usually I work with clients who want to improve their performance in some way. A useful way of thinking about this is the "Inner Game" (Tim Gallwey) equation:

Performance = Capability/Potential — (minus) Interference

Interference can be both internal and external; but here the interference is internal impostor feelings/thoughts. But what are they, where do they come from and how do we manage them to minimize their impact on performance?

What is Impostor Syndrome (IP)?

In 1978, doctors Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes conducted a piece of clinical research[3] with 150 High Achieving Women who were not, shall we say, enjoying the fruits of their roles. What Clance and Imes discovered was that the normal feeling of discomfort that we all feel when embarking on a new situation would trigger overwhelming doubt and uncertainty in these highly successful women. Despite evidence to the contrary, the women discounted their considerable achievements and were insistent that they just didn't belong — they were frauds and would be found out at any moment. At the time, it was thought that IP only applied to women.

Since that time, further research[4] published in the International Journal of Behavioural Science in 2011 shows that 70% of men and women have experienced IP at some point in their lives. That research also showed that millennials may suffer even more as they've started their careers at a time of extreme technological pace where there are constant comparisons on social media between group members.

Those suffering from IP are actually good at what they do.

How does it feel to have IP?

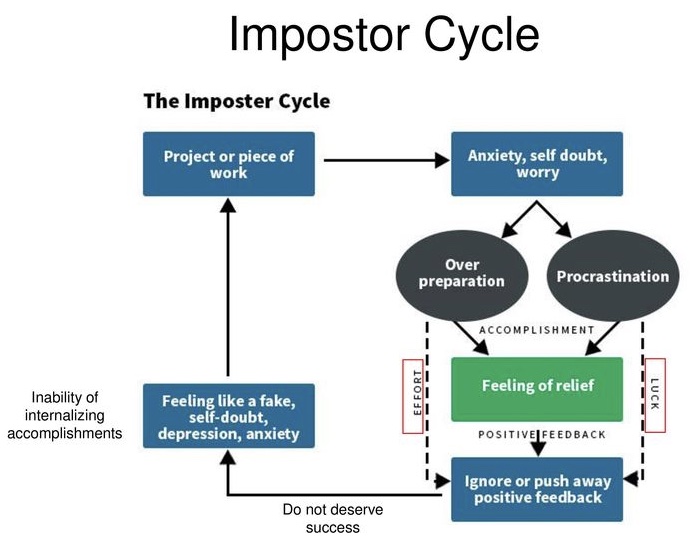

In 1985, building on their earlier research, Clance produced the Impostor Cycle (see diagram) to represent the self-reinforcing nature of IP.

Source: Sakulku & Alexander (2011)

Regardless of positive feedback, their subjects' sense of perceived fraudulence would increase with every new project or task they were asked to perform. Every success became a vicious cycle of self-doubt and anxiety, followed by over working, perfectionism or procrastination.

Those suffering from IP are actually good at what they do. They are asked to take part in new projects or get involved in something new relatively often. They won't say no — or say no very rarely — because they frequently have strong people-pleasing styles, perfectionism and work ethic. After saying yes, they will either spend weeks over-preparing (yet still not feeling like it's enough) or totally ignore it (hoping it might disappear) and they 'wing it' at the last minute and put the success down to luck of the gods.

These individuals won't enjoy the outcome or the delivery of their efforts, despite doing a great job, and will tend to ruminate on the one thing that didn't quite got to perfection. No one else will be aware of this internal nightmare so it's likely they'll be asked again next time. And on and on it goes....

Different Types of Impostor

Valerie Young[5] posited there are 5 types of Impostor:

- The Perfectionist

- The Soloist

- The Expert

- The Natural Genius (great Mind)

- Superwoman/man

Which one are you — or are you a combination of two or more?

Source: Valerie Young

A Personal Reflection: Where do IP feelings come from?

Let's take a trip back in time to my very young self. I was a bit of a plain Jayne at school, a very small, high achieving swot (British term for someone who studies a lot) — I daren't be anything else in all honesty. To fail at anything, especially if my normal giggly and 'acting the fool' self got in the way, meant a good hiding (aka beating) from my dad. I am not saying this to shock you but to make you realize my context for failure — in this case, failure meant an actual beating or even the the fear of a beating.

Also implied, although never stated, was the withdrawal of love, feeling of disgust and of letting down my family. Of being not good enough.

Failing was only one of the reasons I got a beating (my brother fared the same as me). Other reasons included:

- I spoke out of turn

- I spoke at all

- I laughed when I shouldn't have (to this day I don't understand this)

- I didn't do what I was supposed to have done (the 'doing' being so illogical it was hard to remember or predict)

- Wearing the wrong thing

- Doing the wrong thing, at the wrong time

- Being alive (it felt this way at times)

On top of this constant fear at home was an added dose of bullying at school; because I was short, awkward, and a swot.

Did I know who I was really? Nope, not one clue. I was so shut down and scared the only outlet for me was acting and dancing (and the dancing was taken away at age 13). Acting was great because I got to be someone else for a few hours and that was a glorious escape. I'm not telling you this for pity but to outline that fear from a young age — consistent, systematic fear — will cause trauma of varying intensity.

Trauma is not easy to deal with (especially if you don't realize you have it). How it showed up for me is that I was on constant high alert (e.g., my amygdala was poised for flight, fight, or freeze), I would come across as highly defensive, and I definitely felt like I was worthless and not good at, or for, anything. Being good at drama didn't really count because that wasn't really me.

Despite all this (or maybe because the impetus to leave was so great) I ended up leaving home at age 18 and going off to pursue a degree in English and Drama in University, armed with 8 O'levels and 4 A'Levels. I was the first person in our family to ever go to University (I'm glad to say I was not the last). I didn't have anyone beating me to do well, but I still achieved a 2:1. Did I believe I deserved it though? No, not at the time. I thought I had winged it, that it was a fluke. Does this sound familiar?

I was a northern, working class girl with a 2:1 degree and I was a fish out of most of the water I swam in. I was always good at what I turned my hand to at work, but in all honesty I never felt like I belonged and I was waiting to be found out.

Summary of Reasons for IP

Since the original research, factors that contribute to IP have been outlined as:

1. Gender

While there are more opportunities for women leaders since 1978, we know there's still a long way to go. Being a woman means we're in the world's largest 'outgroup' psychologically speaking.

2. Status/Background

Belonging and roots matter when considering the feelings of fraudulence. If you don't fit anywhere, the feelings associated with IP will be amplified.

3. Culture/Ethnicity

Research has since shown that women leaders from ethnic backgrounds present with higher incidences of IP. Not only do they have to contend with the issues of gender stereotyping and in extreme cases racism, these women also often discount their achievements due to positive discrimination, or 'making up the numbers'.

4. Dominant Groups

A sense of belonging and the need for a 'tribe' is now being more widely researched within the wellbeing sector, as it is understood that it's an essential aspect of high-performance functioning.

5. Attachment Style

This is often connected to childhood attachment style[6] or from other positive and negative experiences throughout childhood. For example, if we receive love for doing well at school, then we'll try and replicate that behaviour, believing that doing well = love; if you're not doing well, you will feel you are not good enough or not worthy of love.

6. Fear

The fear of 'being found out' or 'not being good enough' is so strong and real to the Impostor that they never question it. To understand why, we need to look at how our brains are wired and the original function of our fear response. Our brains are wired for threat and reward; it's our very own survival operating system. Our threat system (the amygdala) is triggered when we feel fear, anxiety or stress, usually at the unconscious level, and that in turn sets off a fight/flight/freeze reaction in our bodies.

Unfortunately, the amygdala is a bit like an oversensitive burglar alarm and it cannot differentiate between an actual threat and a perceived threat. In other words, the fight/flight/freeze response can be triggered when all we need to flee from is our own thoughts. It's like when we watch a scary film, we know that it's not real but our response is still very real to us. Then add in the physical sensations like increased heart rate, sweaty palms, knots in the stomach, tension, heat, etc. and it's almost impossible to not think it's real.

Thoughts are not facts, however, and nothing dramatic has changed. You're still the same person you were a few seconds before — the same person with considerable competence, strengths, and abilities.

7. Beliefs

Meanwhile, our beliefs have been created over time in response to conditions in our childhood. To understand why these beliefs become so entrenched, when they are clearly not good for us, we need to look to confirmation bias. In a nutshell, when we see information that supports our current belief, we take it on whilst ignoring and discounting anything that conflicts with our world view. In addition, beliefs which are set with strong negative emotions (such as IP) are even more resistant to change because of our survival instinct. Impostors think the over-working and procrastination is keeping them safe, whilst in truth the very opposite is happening.

It has taken me a long time to let the perfection go — to realize I'm ok just as I am. My good enough is just that.

Failure was not an option in my childhood, and this created a perfectionist, sometimes super-human, often soloist beast that has been driven by fear.

What might help?

Counseling worked for me. I forgave my parents as they were also victims of their own upbringing and attachment experiences. It helped me to put this into context. I now notice when my defenses are up and I am able to work out why. I call my past trauma echoes in my bones, because whilst on the whole it doesn't define me, now and again I catch a glimpse of the old responses waving in the background. They pop their head up and are gone as quickly.

Here's what other clients tell me they have found useful (I still keep a dossier of all my 'good stuff' although I find I look at it with different eyes now).

Become an archaeologist of your own narrative history. —Jayne Rooke

1. Know the beast

Sometimes awareness and knowing that you're not on your own is enough to spur a different approach. Above all, be patient and kind to yourself. You've been living with these beliefs all your adult life and it might take time to change them.

2. Become a first-class noticer

When does your impostor come out to play? Are there certain people or situations when this is more likely to happen for you? What frame of mind are you in? What is your overall wellbeing at this point? What thoughts and beliefs are running through your head? Journal or write these insights down, as near as you can to the moment they occur. Become an archaeologist of your own narrative history.

3. Evaluate your beliefs

Are your beliefs working for you or against you? We re-evaluate our relationships, goals, progress, career, etc. on a regular basis, why wouldn't we do the same for how we think about ourselves? What messages did you receive as a child about your achievements, importance, mistakes or values? What was your family's definition of success? What if all these experiences and resulting beliefs weren't right in the first place? Who could you be without these beliefs?

4. Log your successes

You can be as creative as you like as you log your successes: write, draw, mood board, timeline ALL your successes and keep adding to your list.

Successes can include your qualifications, job promotions, salary increases/bonuses, compliments, praise, voluntary work, difficult situations handled well, presentations given, positive feedback, or personal success in hobbies or family.

I keep a journal/scrapbook of thank-yous, notes, testimonials, and all the things that have brought me joy and a sense of pride.

Another approach I use when coaching clients is to create a list of "X Things I Like About Me"[7], where the X stands for your age. This can include anything from the way you think, your attitude, values, personality, strengths, skills or your physical appearance. You can even involve others in your quest and keep adding an extra item every time you have a birthday (an extra birthday present to yourself).

5. Feel gratitude

I recommend daily gratitude writing or journaling. I use an app called Presently[8] and every night before I go to bed, I sit and write down everything I have been grateful for that day.

It's the little moments that make a big difference to changing the way you think about yourself and the lives around you.

6. Stop procrastination

Start with your why and visualize how good it will feel when you have completed the project/task.

Break your objective down into manageable steps — what is the first step you need to take to make a start? Diarize it. Do it. If something takes less than 2 minutes, do it immediately.

"Eat that frog"[9] Do the hard things first. Don't be tempted to check emails first thing if that's when you're at your best.

Set a timer (Pomodoro Technique[10]) and work on the project/task for 30 minutes then allow a break.

Layer in accountability and let others know about your plans. Get a cheerleader or accountability partner to hold you to that plan.

For Soloists who are struggling with asking for help on this, reframe the request as a "need for the project" versus a personal need. It will help you think differently and might take you away from 'I am an Island' beliefs.

7. Move from perfection to good enough

Perfection doesn't exist. If you are setting a completely unrealistic bar for yourself, you will never be happy.

If you're leading a team, think about the impact your pursuit of perfection is having on those around you.

Who said things had to be 'perfect'? What's important to you and what could you let go or delegate?

Be crystal clear about what deserves your attention. If you're still struggling, reframe the idea of perfection into an idea of efficiency. Is it efficient for everything to be perfect and take three times as long? Where did that belief come from?

Aim for 80% and stop agonizing over the last 20%!

When reviewing projects start with what has gone well, what could be different, and identify the lessons learned. Don't start with what wasn't perfect.

Experiment with letting it go and you won't be disappointed. Trust me on this one, it was a revelation to me and life got a whole lot easier after I realized there was no imaginary bar to start with.

8. Be kind to yourself

As Zig Ziglar said, "You are the most important person you will talk to all day."

When you are in free-fall, stop and ask yourself, "Would I say that to someone else out loud?" The answer is usually no.

Instead of "I am rubbish at..." try "I can't do that yet."

What advice would you give to your best friend, family member or son/daughter right now? Does your Impostor have a voice or do they remind you of someone?

Could you draw a picture of your Impostor and give it a name? (I once left mine on a train, and have also locked her in a cupboard when I needed to start an important piece of work while she was distracting me.)

9. Learn how to fail

Failing is part of growth. It's ok to not get it right all the time. What beliefs are at play here?

Instead of "I have failed," try, "What I have learned today is..." or, "I will do X differently next time."

Give yourself permission to get things wrong. Seek out experiences where you will fail, because you're new at it.

Undo those 'failure is not an option' beliefs and see what happens. Eliminate that phrase.

10. Embrace vulnerability

This is similar to the tip on failure, but is more about how we see ourselves.

We all have doubts at some time or another. It is ok to not have all the answers — or any of the answers. In a world that is constantly changing, how can we? Focus on what you can do and what you do to contribute.

Try saying "This is new to me, I don't know," or "I'm not there yet, but I'm making good progress." I guarantee the person sitting opposite you will thank you for it and your relationships will be strengthened, too.

If you're frightened to fail, you won't try anything new. We need experimentation and new endeavors for innovation and creativity to occur.

Summary

What I know from delivering over 1500 hours of coaching is that the majority of working professionals I've met, many of whom have been in Director and C-suite level positions, experience Impostor Syndrome at some point or another. It doesn't have to be this way. You can overcome it by better understanding your fears, replacing them with more helpful responses, and by challenging entrenched beliefs.

This will take work and practice — there is no quick fix, but it is fixable if you are willing to put yourself under the microscope.

I can't say I never get IP feelings anymore, but I know them for what they are and choose to not let them keep me small. I hope that one of these strategies will help you to do the same.

NOTES:

- [1] Impostor Syndrome is a misnomer — it is not consistent so therefore is not a syndrome but a phenomenon, hence the IP abbreviation throughout this article

- [2] https://hbr.org/2005/09/the-dangers-of-feeling-like-a-fake

- [3] https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1979-26502-001

- [4] https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/IJBS/article/view/521

- [5] Young, V., (2011) 'The Secret Thoughts of Successful Women: Why Capable People Suffer from the Impostor Syndrome and How to Thrive in Spite of it', Crown Publishing

- [6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attachment_theory

- [7] McMahon, G. et al (2010), 101 Coaching Strategies and Techniques, Routledge

- [8] https://presently-app.firebaseapp.com/

- [9] https://todoist.com/productivity-methods/eat-the-frog

- [10] https://todoist.com/productivity-methods/pomodoro-technique

Go to eRep.com/core-values-index/ to learn more about the CVI or to take the Core Values Index assessment.

Jayne Rooke

Contributor

Jayne Rooke is an Executive Coach specialising in wellbeing, leadership and developmental coaching. She has run Peak Potential Consulting since 2012 and works with individuals and teams in a variety of sectors.

View additional articles by this contributor

Essentials

Additional Reading

Stay Updated

Employer Account Sign-up

Sign up for an employer account and get these features and functions right away:

- Unlimited Job Listings on eRep.com

- Applicant Search

- Applicant Tracking System (ATS)

- Unlimited Happiness Index employee surveys

- 3 full/comprehensive CVIs™

- No credit card required — no long-term commitment — cancel at any time